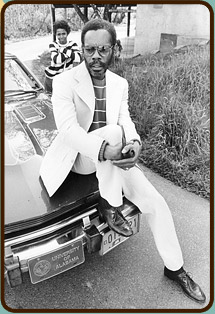

The Old Huggin' Man (0:15)

"Grandfather"

Leonard Smith

There's nothing that I see that I don't like about the neighborhood. I'm so proud of this neighborhood. We have a spelling bee for the kids, we have a spelling bee for the adults at the Mississippi--and I'm the old huggin' man. I hug the kids and when you lose, I give you a hug.

There's nothing that I see that I don't like about the neighborhood. I'm so proud of this neighborhood. We have a spelling bee for the kids, we have a spelling bee for the adults at the Mississippi--and I'm the old huggin' man. I hug the kids and when you lose, I give you a hug.

Audio Links

- egf1.mp3

- egf2.mp3

- egf3.mp3

- egf4.mp3

- egf5.mp3

- egf6.mp3

- egf7.mp3

- egf8.mp3

- egf9.mp3

- egf10.mp3

- egf11.mp3

Audio Titles

- Grandfather Leonard Smith, born saw mill town Alabama.mp3 (1:45)

- Did you ever get into trouble growing up? (0:57)

- How is the world different now? (1:00)

- Civil Rights movement stories (1:20)

- The police would not come here (3:56)

- The first neighborhood block party (2:50)

- The Mississippi Street Fair (0:59)

- I'm the old huggin' man (1:26)

- It's your future (1:15)

- I'm just one lucky old man (1:01)

- Old huggin' man (0:15)

Text of Audio Links

- Can you please tell me your full name?

Leonard Smith

Where were you born?

A sawmill town called Vredenburgh, Alabama, 1937.

Did you enjoy living there?

Yes, where I grew up was pretty unique, because today there's not more than a hundred people living there and when I grew up there was never more than 200. And our town is a sawmill town, it has a black quarter and a white quarter--still has that today. And we're kind of the luckiest people in the world because there's no child had a better Christmas than me.

When I tell people I'm from Alabama they go, "Wow, must have been horrible." It's the greatest life in the world, because today I have never faced things that you guys have faced--hardships or racism--I never faced that, see. Today we own the property that we always had because the sawmill gave it to the people that worked for them. My parents didn't work for the sawmill, they were teachers, and my dad was a mailman, so we were a little fortunate than other people, but everyone was kind of the same.

In Christmas time we had a huge Christmas tree just like they had in D.C. and we had huge boxes of fruit and you could just get how many boxes you wanted, just plenty. And we had a Santa Claus, just like they do in D.C. today. And we didn't have any crime. Today in my city there's been one person killed there in all these years. We don't have crime. There's just nothing there. - Did you ever get in trouble when you were growing up?

No, no, no. There was no trouble to get in. You had to--here we talk about summer jobs, right? And when you hear people talk about picking cotton, people think that picking cotton was a slave thing. It wasn't a slave thing. And if you wanted to make any money, you either had to go and pick cotton, beans, you know, tobacco, those things. They was the only kind of summer jobs you could have--not for just black kids, but for any kid to make money to buy your school clothes for the next year. There was no trouble.

I never had a drink of liquor until I was in the military.

Tell me about the military.

I didn't like the military. I still don't today. I don't think that we need to kill people. I think we can do better than that. - How is the world different now than when you were a child?

It's not, it's the same. The difference is today that--technology. See where I grew up we didn't have no electricity, we didn't have no indoor toilets--some people still don't today. And there was a very few cars. I don't have a birth certificate today because midwives--and you know when I grew up there was storm seasons--and she only had a mule and a wagon to get across the cricks, as we say. Because cricks shut us off from each other and its kind of hard to get across them when the water rise, so I always used to wade across them, so she had to try to get across the crick and get back home, so she didn't have time to fill out the necessary papers for a birth certificate so most of the kids where I come from don't have birth certificates. And I'm in a war with the government right now trying to get my passport. - What were some experiences during the Civil Rights movement?

I didn't participate during the Civil Rights movement because I was, I would have been violent and Martin Luther King said we couldn't. He didn't want us in because we were violent. I won't turn this cheek.

And so we went to these places. I was in Selma. I saw the police shoot the lady down in Selma, Alabama on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. And I couldn't stand that and just saying no, no, no, so that's why I did that.

And then my Dad said, my Dad said, "Why would you go and fight to sit in Kresky's where the roaches and rats are running around--it was this lunch counter--he said, "If you want a place that don't nobody want you in, build your own."

We had the water fountains, and they had "Coloured" and "White" only. And my Dad said, "If you drink out of the water fountain, you make sure you drink coloured." And today I don't drink water. I don't drink water. Today.

So those are things that I learned from my dad: that if somebody don't want you, keep going, do your own. And that's how I am today. - When I came here in 1985, the police would not come here. Every building on this street but this one, there was a bar. And on the corner, Betty Campbell building, that was the stripper bar and the grocery store. And the coffee house on the other side, that was the tax office and the drug store, and I bought the building across the street. And that's when everything hit the fan.

There was like 200 people all the time on this street so that's why I'm saying, "Oh wow, good place for a restaurant," you know. And that's when I come to find out they were not the best kind of people in the world. And that was 1985.

So you chose the Mississippi Street because you thought you would have a lot of business, right? But what was the consequence that you weren't planning?

Nothing that I planned happened. First thing, the liquor commissioner refused me a liquor license because of the "element" on the street. At the time, my argument was with the mayor that the police is not doing their job. See, every day the corner was full of people. They were selling drugs, they were prostituting. Whatever was going on bad, was here.

These are dentures because a man knocked my teeth out. Police wouldn't come. So then, the old Alabama in me came out. I got mad. So I went downtown--I went to City Hall. And I had a sign on my back, it said, "Man, they sell drugs in front of my place. Why?" so Bud Clark wouldn't talk to me. But every morning I was in front of city hall.

You know, I didn't have a permit. But I knew what I gotta do--I gotta go ahead and make friends with somebody. So I went inside--you know in City Hall they got these little chairs for their visitors to sit--so I sat there. And I'd tell the bodyguards, "You know I'm harmless! So don't kill me or don't, you know, do bad things to me." And he said, "No, you're okay." And so we became good friends. So I went there every morning.

Until one day the kid got shot. This meeting and all this is no good. I'm saying, "Sir, you got ten days to do something about this, if not I'm going to go to Salem to get the National Guards to come in." He didn't know I was that smart. So sure enough, ten days came, I went down to Salem, they brought the National Guard to Portland to stop this situation. Then Bud Clark talked to me. So finally we became good friends. He gave me two police officers and I gave them keys to my building, they would go up into the building--then NBC got involved. And they would film the drug dealers and the prostitution out of the window. And then they had the police around and they would just kind of go sweep them up. So then they all knew that I was doing this. And that's when they broke out every window right there in my building. They just took a stick, went and broke all the windows out of it. So I'm saying, "That's fine, we'll put some more windows in."

Then they--a kid got killed at the Laundromat down on the corner. And that was the first time anyone came to my rescue and it was the Kellys--Neil Kelly--they owned the building diagonal across the street from that Laundromat, so they got--it used to be the Rejuvenation house--so then they got involved, and that's when we began to get some things going, because the older gentleman, Neil Kelly, was on the City Council.

And every morning on his way to City Council meeting he and I would stop, we would sit on the corner of Mississippi and Shaver and I would tell him what we needed to do downtown. And that's when they flooded the neighborhood with the police and kind of got things under control. - Can you tell me about the first time you tried to organize a neighborhood block party, why you tried to organize it?

- I was listening to the news, right, and the news say, if you live in the neighborhood, get all the neighbors together, have a block party and interact with the police because nobody trusts the police. So I went around all day, man, I was running around and finally that night, some kids they had a band, and I was at the Equinox building then, lined the band up and when the music started, people from the neighborhood started coming--people that never came on that corner come out to the neighborhood. We was just having a party. And we were waiting for the police to come, because they was supposed to come interact with us. So maybe half an hour after we started, the police did come and they had their lights on and we thought, "Oh, man, this is really neat," you know? And then when they came, you know, we were dancing on the car, we were dancing on the streets, and then they asked for me. And they took me and threw me on the car. And they handcuffed me. I said, "What are you doing?!" I thought they were just joking, you know. They went and got all the band members--these are kids--and they handcuffed them and took us to jail. And I was saying, "Oh, wow." So then when I went to jail, I kind of refused to participate in the trial.

And I told the judge, I said, "You know, I'll tell the court a story, but I'm not here to be tried and if you want to send me to jail, we'll go now."

So the judge said, "Well, you the only person who ever said something like that to me."

And I said, "I know, but that's the chance I got to take."

And he said, "We'll listen to you."

And I told him, "Sir, I heard that we were supposed to have a block party--get together, you know what I mean." I said, "I live in the worst neigh…"

He said, "We know your neighborhood."

I said, "I was just trying to get my people together, come together and have some fun and maybe we can get with the police and do something."

And then he asked the police and said, "Is that kind of what happened?"

And he said, "That's just what happened."

And he said, "Well, it sound like to me, that this young man is over here fighting, trying to improve his community and you guys screwed up the best party they ever had."

And they dismissed it.

So, that's what happened. But then, the kids lost thousands of dollars worth of equipment--their drums--because they police would not allow us to put it inside. They just hauled us off to jail. So that was pretty bad for me.

So the equipment got pretty much stolen or something?

Yeah, because you know there was nothing here but gang members at that time. So they just took everything they needed, including in the store, you know. I've been broke three times, on this street. - If you were hurt, why did you stay on this street?

Because I knew it could be something. Last year at the street fair, I looked down that street and I saw this street packed--must have been 10,000 people on this street. They couldn't have come here without me; you wouldn't have come on the Avenue. The drug dealers, it was like the barrio in New York--I don't know if you know the barrio in New York--when the car stops, they start washing your windows and you gotta pay them. Well, they were there when the car stops--at Shaver that used to be a red light--and when you stopped your car for the red light, they'll rush your car selling you drugs. They didn't know if you were the police--they didn't care. They sell you drugs and you intimidated so you buy them. Like now, we have panhandling going on, some people are so intimidated, they just give them the money. And I saw that this could be stopped, and this could be a nice, viable neighborhood like it is now. - So what would you like to see happen to this neighborhood, now that you're not here?

I'm here!

I mean, like, you don't live in this area, you don't own a business. What would you like to see happen?

I don't know if you know, I'm not an owner, but I'm a part of the Mississippi Pizza. Philip is like my son.

We have a spelling bee for the kids, we have a spelling bee for the adults at the Mississippi--and I'm the old huggin' man. I hug the kids and when you lose, I give you a hug.

At this Street Fair Day we still have the Rib-Off that I started. I'm a cook, I cook ribs, right? So what I do every year we have the Rib-Off here for the Street Fair. So Grandfather ain't going nowhere, you know? This is my street.

I just live in Vancouver, that's where my grandkids are. When I did leave, they wrote an article about me, "Mr. Smith goes to Washington." That's a neat one, eh?

So what are some things you still don't like about this neighborhood?

There's nothing that I see that I don't like about the neighborhood. I've always been proud of Boise because it's one of the best schools I've seen. I'm so proud of this neighborhood. - Is there anything else you would like to add that I haven't asked, that you would want us to know?

No, I just want you guys to know that you need to get involved, you know.

It's sad, I just saw a young lady the other day--twenty-some years now she's doing the same thing, I'm talking about walking through the neighborhood. They are prostituting. I gave her a big hug. I don't hate her because she's that way, you know what I mean? You wouldn't know who she is, you know, but I do, see. So that's what is happening to our neighborhood, see? These people--they're part of it, they live here, see--I think that people ought to be able to come home, but they've got to behave according to the rules, see? We had to do it.

So, I don't know the answers to all the things that, you know, happen, but there are answers.

And you young folks need to stand up and rally about it. When you seeing these things, when you see it, tell it--tell it. Don't be afraid. That's what happened to me, see? Had I listened to the kids, the guys here on this avenue, I would have been just like them, selling drugs. I would have been the same as them. But I never would do that, see. It's your future. - Reflecting on your life, is it how you imagined it would be?

I couldn't ask for no more love from people like Brian [Steelman from Por Qué No] and Philip [Stanton at Mississippi Pizza] and these guys. So I got all kinds of love. I'm 71 years old and the only problem I have in my life is a bad lung. You know how I got that? Smoking cigarettes. My doctor asked me, "Are you ever depressed?" and I said, "Yes." She says, "When?" I say, "When I buy a lottery ticket and it says, 'Sorry, not a winner.'" Other than, I'm never depressed. I got nothing to be depressed about. You know what I'm saying?

I'm just one lucky old man--but I have worked hard for it. And I'm proud of the work I've done. I don't think some of the things I've done that--I never wanted to hurt anybody but I didn't want to die either, so those things that I've done, I'm sorry, but they had to be done--or it was me.

So, other than that, I'm proud and happy.  There's nothing that I see that I don't like about the neighborhood. I'm so proud of this neighborhood. We have a spelling bee for the kids, we have a spelling bee for the adults at the Mississippi--and I'm the old huggin' man. I hug the kids and when you lose, I give you a hug.

There's nothing that I see that I don't like about the neighborhood. I'm so proud of this neighborhood. We have a spelling bee for the kids, we have a spelling bee for the adults at the Mississippi--and I'm the old huggin' man. I hug the kids and when you lose, I give you a hug.